Return to biline.ca Audio/Video Section

Read some articles from The Audio Critic Magazine.

The Audio Critic: Web ’Zine - Page 2

Electronic Personality?

26 April, 2007

Electronic Signal Paths Do Not Have a Personality!

I keep forgetting that my newer readers outnumber the old-timers and that some of the basic truths about audio that are old hat to me and to the regulars are new and fresh to the recent arrivals. Here is something, therefore, worth repeating for the nth time.

Every low-distortion electronic signal path sounds like every other. The equipment reviewers who hear differences in soundstaging, front-to-back depth, image height, separation of instruments, etc., etc., between this and that preamplifier, CD player, or power amplifier are totally delusional. Such differences belong strictly to the domain of loudspeakers. Depending on the wave-launch characteristics, polar pattern, or power response of the loudspeaker (those are overlapping concepts), the stereo presentation of the program material can vary greatly. It cannot vary as a result of the properties of a normal (i.e., low-distortion) electronic signal path. The only exception I can think of would be totally inadequate channel separation (less than, say, 30 dB) between the left and right channels of a stereo device, which is hardly ever the case—and certainly not when high-end components are being discussed by said reviewers.

Beware, therefore, of electronic audio components with a personality. If they have a personality, they are either defective or the brainchild of a reviewer without accountability.

New A/B Technique

27 February, 2007

A New, and in Some Ways Preferable, A/B Comparison Technique

I have believed for decades now that the only scientifically valid technique of A/B-ing two audio components against each other was a double-blind ABX listening comparison at matched levels. Now Bill Waslo of Liberty Instruments has come up with a new methodology that has the potential of being more widely used because it is simpler, takes less time and less fussing, and is basically automated.

The essence of the process is this: Record the output of an audio component when playing any piece of music, or even a test signal. Then change something in the system—a cable, an amplifier, any other component, or apply an audiophile tweak of any kind. Next, record the output again with the same piece of music or the same test signal. Then, using Bill Waslo’s “Audio DiffMaker” software (which has not been commercially released yet but can be downloaded in a trial version), align the two recorded tracks to the same gain level and timing. Finally, subtract one from the other and listen to the difference recording. If it is basically silent, then the change has clearly done nothing. No sound in the difference recording means that the change has made no difference. If the track is not silent, then a difference may have been made by the change, and further investigation is warranted.

A simple schematic of the process is the following, courtesy of Liberty Instruments:  Now, I am not saying (and neither does Bill Waslo) that Audio DiffMaker will convince the flat-earthers who remain unconvinced by ABX listening comparisons. There is such a thing as invincible ignorance. What I am saying is that AudioDiffmaker is scientifically sound, more convenient than ABX (automatic level matching, no endless iterations, etc.), and considerably more sensitive than the human ear. The difference recording may in some cases have a tiny signal on it below the threshold of audibility. The important thing from the audio point of view is—can you hear the difference? Listening directly to the difference, and only the difference, instead of iterated A/B comparisons is the main advantage of Audio DiffMaker. It will be interesting to see whether this new technique takes off, at least in electroacoustically sophisticated circles. Much more detailed information is available by going to http://libinst.com/Audio%20DiffMaker.htm.

Now, I am not saying (and neither does Bill Waslo) that Audio DiffMaker will convince the flat-earthers who remain unconvinced by ABX listening comparisons. There is such a thing as invincible ignorance. What I am saying is that AudioDiffmaker is scientifically sound, more convenient than ABX (automatic level matching, no endless iterations, etc.), and considerably more sensitive than the human ear. The difference recording may in some cases have a tiny signal on it below the threshold of audibility. The important thing from the audio point of view is—can you hear the difference? Listening directly to the difference, and only the difference, instead of iterated A/B comparisons is the main advantage of Audio DiffMaker. It will be interesting to see whether this new technique takes off, at least in electroacoustically sophisticated circles. Much more detailed information is available by going to http://libinst.com/Audio%20DiffMaker.htm.

CD/SACD Reviews

01 January, 2007

CD/SACD Reviews

As always, I am reviewing only those CDs, new or fairly recent, that I found interesting. (Sometimes even a bad performance can be interesting.) Just because they sent me a review copy is insufficient reason for a review in this Web ’zine; there are plenty of other reviewers out there who will oblige.

SACD from Channel Classics

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor (“Resurrection”). Birgit Remmert, mezzosoprano/alto; Lisa Milne, soprano; Hungarian Radio Choir; Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, conductor. CCS SA 23506 (2 SACDs, recorded 2005, released 2006).

“A symphony should be like the world: it must embrace everything,” Mahler is supposed to have said, and the Second is the earliest gigantic work reflecting that creed, still completely free from the mannerisms and self-indulgence of some of the later symphonies. You don’t have to be a Mahlerian to love the Second (or the Third). This recording by Iván Fischer is a sequel to that of the Sixth reviewed here about a year ago, made with the same orchestra and technical crew in the state-of-the-art Béla Bartók National Concert Hall in the Palace of Arts in Budapest. I will not repeat my encomiums regarding the hall, suspect as they were of Hungarian chauvinism, but I must reluctantly admit that the Mahler recording in Philadelphia’s comparable Verizon Hall (see below) sounds even a little better, especially the 5.0 layer, although this one too is very high-class audio. Fischer’s performance once again emphasizes the big line, the totality of the work; he conducts the forest, not the trees (again, see below). The soloists and the choir are excellent. Of course, the competition in Mahler Seconds is huge. Speaking of Philadelphia, Fischer guest-conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra recently and made a tremendous impression. The musicians loved him. Does this mean he is a dark horse to follow Eschenbach when the latter retires after the 2007-08 season? No one says so, but you heard it here first…

CD from EMI

Carl Orff: Carmina Burana. Sally Matthews, soprano; Lawrence Brownlee, tenor; Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Rundfunkchor Berlin; Berliner Philharmoniker, Sir Simon Rattle, conductor. 7243 5 57888 2 5 (recorded 2004, released 2005).A poor performance of Carmina Burana is almost impossible; everybody employing the required forces does a more or less decent job because the piece is totally simplistic—no harmony, no counterpoint, simple rhythms, unison singing, unsubtle aggressive percussion. That the piece is so effective is utterly amazing (must be the catchy tunes). The best performances are characterized by high energy to the point of wild abandon, combined with precise execution plus superior singing. This is definitely one of those best performances, and since the live stereo recording is also excellent, one of the better efforts in the tricky Philharmonie, the whole production must be rated as top rung. The awesome competence of Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic is almost overkill for the piece. Baritone Christian Gerhaher is a standout, better than most singers in the role. If you don’t have a recording of this oddball quasi-masterpiece, you might as well get this one.

SACD from the Fry Street Quartet

Joseph Haydn: String Quartet in D Minor, Op. 9, No. 4; String Quartet in F Major, Op. 77, No. 2. The Fry Street Quartet (Jessica Guideri, violin; Rebecca McFaul, violin; Russell Fallstad, viola; Anne Francis, cello). FSQCD4 (recorded 2005, released 2006).This is another IsoMike recording by Ray Kimber under the Fry Street Quartet label. The first one I reviewed here some time ago and declared it to be the new “state of the art” in chamber-music recording, surpassing all previous efforts in realistic, lifelike string sound. This one is even a little better, if such a thing is possible. The warmth, the presence, the sheer you-are-thereness of the violins, viola, and cello are unprecedented. (Yes, Ray, your cable marketing sins are forgiven.) Op. 77, No. 2, dating from 1799, is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, string quartet of Haydn, an absolutely stunning work surpassed only by the best of Beethoven (whose earliest quartets are roughly contemporaneous). Op. 9, No. 4, composed some thirty years earlier, is good music but not quite in the same league. The Fry Street Quartet, as I wrote before, is as good as some of the big names that are much better known. They play with superb musicality and unfailing beauty of tone. For a wonderful musical experience and a unique audio treat, get this CD. (I like the stereo layer at least as much as the 4-channel surround layer.)

CD from Harmonia Mundi

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 4 in E-flat Major (“Romantic,” 1878/80 revision, ed. Nowak). Orchestre des Champs-Élysées, Philippe Herreweghe, conductor. HMC 901921 (recorded 2005, released 2006).

This one is controversial. Like Herreweghe’s recording of the Seventh reviewed here several installments ago, it is “Bruckner Lite,” and you have the right to love it or hate it. I happen to think that the added transparency achieved with 19th-century instruments and the nonpompous treatment of the musical material yield a highly viable alternative to the monumental Bruckner style. Bruckner may have been a Wagnerian but he was no Wagner; the Götterdämmerung approach to some his passages runs the risk of self-parody if the conductor isn’t careful. Emphasizing the classical side of the music isn’t such a bad idea. I still want to hear the Karajan kind of Bruckner from time to time, but Herreweghe’s approach is refreshing. The stereo recording in a smallish auditorium in Dijon is very realistic of its kind.

CDs from Naxos

Béla Bartók: Mikrokosmos (Complete): Books 1–6. Jenö Jandó, piano. 8.557821-22 (2 CDs, recorded 2005, released 2006).

Not for the fainthearted—153 increasingly complex piano pieces, ranging from the naïvest simplicity to diabolic virtuoso exercises, the shortest lasting 16 seconds, the longest over 4½ minutes. No other composer has tried anything remotely like it; most of it is of pedagogical importance rather than concert-hall material, but Books 5 and 6 contain some brilliant performance pieces. Bartók’s utter devotion to the essence of music, without the slightest attention to the possibility of worldly success, could not be better exemplified than by this monumental work. Jandó is a well-established Bartókian, and I hear nothing to fault in his performance, right up to the virtuoso rendering of the terminal complexities. The recording of the piano is close-up and extremely real, typical of the work of the excellent Phoenix Studio in Budapest.

Aaron Copland: Prairie Journal (1937); Rodeo: Four Dance Episodes (1942); Letter from Home (1944); The Red Pony—Film Music: Suite (1948). Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, JoAnn Falletta, conductor. 8.559240 (recorded 2005, released 2006).

Big surprise. The Buffalo Philharmonic is a very high-quality orchestra; JoAnn Falletta is an excellent conductor; Kleinhans Music Hall in Buffalo is a world-class venue. Others may know these things; I didn’t. To perform Copland’s rural/cowboy/American/pop pieces with maximum impact, you have to swing it, not just a little (like, for instance, Michael Tilson Thomas) but a lot. Falletta and the Buffalo musicians dig into it with real gusto, maximizing the rhythms, and it makes a difference. They sound great. As for the audio, my jaw dropped when I listened to the reproduction of the Kleinhans acoustics. How come they don’t make more recordings here? What a great hall! The bass is especially fabulous. This is definitely a CD which is more than meets the eye.

Franz Schubert: Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat Major, D. 929, Op. 100; Sonatensatz in B-flat Major, D. 28. Kungsbacka Piano Trio (Malin Broman, violin; Jesper Svedberg, cello; Simon Crawford-Phillips, piano). 8.555700 (recorded 2003, released 2006).

If you have seen Barry Lyndon, Stanley Kubrick’s great 1975 movie, you probably remember from the soundtrack the haunting andante con moto of the E-flat trio, even if you are unfamiliar with the whole work. It is late Schubert, and that means sublime music, regardless of Deutsch number or opus number. In the last few years of his short life Schubert was in a zone of transcendence. D. 28 is a work of adolescence and not comparable. The Kungsbacka trio, a youngish ensemble that started in Sweden and is based in England, provides an alert and highly transparent performance, maybe a little too foursquare for my taste—I can imagine a more poetic interpretation—but their intonation is flawless. They play every repeat of the sprawling work, stretching it to nearly an hour (not that I’d want it to stop). The violin tone of Malin Broman is occasionally a little wiry, emphasized by the superbly lifelike English recording.

SACD from Ondine

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A Minor; Piano Quartet movement in A Minor (1876). The Philadelphia Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach, conductor; in the quartet, members of The Philadelphia Orchestra (Christoph Eschenbach, piano; David Kim, violin; Choong-Jin Chang, viola; Efe Baltacigil, cello). ODE 1084-5D (2 CD/SACDs, 2005-2006).

Some conductors conduct the forest, others the trees. Toscanini is a good example of the former, Eschenbach of the latter. That’s an oversimplification, of course, because both kinds of conductors, if they are worth their salt, conduct with full awareness of the overall sweep and structure of the piece as well as its details. It’s a question of emphasis. Eschenbach doesn’t reveal anything we didn’t already know about the Mahler Sixth as a totality but he brings out every little detail with amazing lucidity and differentiation. Call it “overconducting”—I love it! I happen to disagree with those who consider this to be Mahler’s greatest symphony but I can’t think of another version I would rather listen to. When Eschenbach leaves Philadelphia at the end of the 2007-08 season, I wonder what great improvements will follow. The sound, too, is superb, the best of the Philadelphia/Ondine series so far. The tunable Verizon Hall has finally been optimized to the nth degree. There are still too many microphones but they are needed for safety; you can’t gamble with “purist” techniques when recording live before an audience. I am completely happy with both the stereo and the multichannel versions; the 5.0 layer is particularly successful in rendering a 3-D space rather than just directional cues.

CD from Profil

Franz Schubert: Symphony No. 9 in C Major, D. 944. Münchner Philharmonker, Günter Wand, conductor. PH06014 (recorded 1993, digitally remastered and released 2006).

Günter Wand has been dead almost five years, but various record labels keep issuing late-in-life recordings by him. This one he made when he was 81 (he died at 90), and for sheer musicality and echt Schubert style it’s a hard-to-beat performance. Wand was a musician’s musician to the end of his life. The tempi are leisurely (Toscanini’s famous Philadelphia Orchestra recording of 1941, for example, is nine minutes faster), but that’s a German super-Kapellmeister’s way with Schubert—noble might be the best word for it—and it works. There are too many recordings of this stupendous symphony to rank this one (Wand alone made several) but it clearly belongs in the upper percentiles. The Munich Philharmonic was not one of Wand’s regular (contractual) orchestras, but he guest-conducted it frequently throughout his life and had an excellent rapport with it, although his Munich recordings could not be legally released before his death. It is an excellent orchestra, just short of world-class, and the stereo recording is also very good, without any eccentricities or exaggerations. The whole effort is an exercise in superior taste.

SACD from RCA Red Seal

Johann Strauss Jr. et al.: “Vienna” (waltzes by Johann Strauss Jr., Josef Strauss, Carl Maria von Weber, and Richard Strauss). Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Fritz Reiner, conductor. 82876-71615-2 (recorded 1957 and 1960, remastered and released 2006).

You think you know how a Viennese waltz should sound? Don’t be too sure. Listen to the very first track on this disc, Morning Papers, Op. 279, of Johann Strauss Jr. Who else beside Reiner conducts a Strauss waltz with this kind of Viennese lilt, with exactly the right hesitation on the second beat and with that infectious exhilaration in the fast passages? Not many, not even most of the conductors of the Wiener Philharmoniker’s annual New Year’s concert (certainly not Zubin Mehta on Jan. 1, 2007). Of course, it helps to have been born in 1888 in Austria-Hungary under Franz Josef. Strauss died in 1899, so little Fritz grew up hearing the real thing. All in all, this is perhaps my all-time favorite Strauss waltz recording, comprising seven pieces by the immortal “Schani” (yes, all the big ones are here), and it even offers extra goodies like the Weber-Berlioz Invitation to the Dance and the Rosenkavalier waltzes. The orchestral playing is awesome, needless to say; the midcentury Chicago orchestra has never been surpassed. As for the audio (this is, after all, an audio journal), it is equally amazing. Lewis Layton, maybe the greatest recording engineer of all time, knew more about microphone placement, hall acoustics, and tape editing fifty years ago than most of today’s top guns with their state-of-the-art equipment. As a result, the soundstage, the instrumental timbres, and the hall effects are as good as today’s best (with maybe just a tad more distortion) and a lot better than today’s average. Orchestra Hall in Chicago, before they renovated it, was probably the most “phonogenic” venue in the United States. The SACD multichannel remastering preserves the original three-channel (left/center/right) recording; the rear channels are silent. I don’t think the center channel makes a huge difference, but the hi-rez DSD technology effects a clear improvement over previous editions. Bottom line: can’t ask for better Strauss or better sound.

Loudspeakers6

25 December, 2006

A Note About Loudspeakers

I have written about this many times before but I keep forgetting that more of my readers are first-timers than longtime habitués. So, even if you know little or nothing else about audio, be aware of this:

The loudspeaker will determine how your music system sounds. Not the amplifier, not the preamplifier, not the CD or DVD player, nothing but the loudspeaker. Speakers, even the finest, are far less accurate in terms of output compared to input than any of those other components. The speaker will be invariably the weakest link in the chain, the link that limits the quality of sound reproduction.

I am always cynically amused when an audiophile brings home a shiny new amplifier in his hot little hands, breathlessly connects it to the dinky little box speakers anything larger than which his spouse won’t allow, and turns on the music. The sound is exactly the same as it was before with his older, cheaper, less fancy amplifier, but of course he will not admit it. If he had spent his money on better loudspeakers instead, the improvement in sound would have been inarguable.

But what is a “better” loudspeaker? The standard model, employing forward-firing dynamic drivers with a passive crossover in a closed box, has been refined to the point where further improvements are most unlikely. There are small ones and big ones, simple ones and elaborate ones, $600 ones and $45,000 ones, but if they are correctly designed (admittedly not always the case), the sound will always be of the same general quality—wide-range, smooth, effortless, but not quite real, with a slightly closed-down, boxy characteristic that says: loudspeaker, not live. There’s a ceiling in performance with this type of loudspeaker, maybe at three or four thousand dollars, above which you get very little, if anything, regardless of the hyperbolic claims and insane prices of some ultrahigh-end models. I have revived the old-time “monkey coffin” label, used by 1970s hi-fi salesmen, for this category of box speakers. There are dinky little monkey coffins and huge expensive monkey coffins, but they all sound like monkey coffins, more or less. If you seek sound that more closely resembles live music, you have to look into loudspeaker designs that depart from the standard model. Two of these have been reviewed in this Web ’zine, the Bang & Olufsen BeoLab 5 and the Linkwitz Lab “Orion.” They are the two best speakers known to me at this juncture, but that doesn’t necessarily mean there aren’t others. I shall try to explore the newer electrostatics, full-range ribbons, powered dynamics with electronic crossovers, etc. Some are not so easy for a reviewer to obtain on loan, especially if he isn’t one of those thinly disguised handmaidens of the industry. We shall see. At any rate, I am through with monkey coffins.

Transparent Fraud

21 October, 2006

A Fraud that Anyone with Common Sense Can See Through

Longtime readers of The Audio Critic are fully aware that many of high-end audio’s articles of faith are bogus. Most of these fraudulent pronouncements about cables, tubes, vinyl, etc., require a little bit of engineering science to refute. A typical example is the absurd practice of biwiring, whose futility is made obvious by the superposition principle, a law of physics not known to everyone (see under downloadable Sample Articles, “The Ten Biggest Lies in Audio,” on this website).

There is one particular audio fraud, however, that requires no science but just ordinary common sense to see through. I’m talking about power cords—yes, those short lengths of flexible insulated cable that go between your wall outlet and your audio gear. The big lie is that they hugely affect the sound. The ads tell you that if you pay $499 or $995 or some such insane amount for a specially designed super cord, you will get a bigger soundstage, better transients, tighter bass, smoother highs, etc., etc., blah, blah, blah. Amazingly, quite a few nonthinking audiophiles with deep pockets buy these fantasy cords.

Now, just think about it. The AC current comes into your residence over miles and miles of wire. After it enters the walls of your house or apartment, it again traverses huge lengths of BX cable or similar wiring. After it comes out of your wall outlet through the power cord and enters your amplifier or other equipment, it again goes through a maze of wiring before activating the devices that affect the sound. So, tell me, how does the electricity know where the nondescript lo-fi wiring stops and the super wire—just six feet of it—starts and leaves off? Does the current say, hey, I’m coming out of the wall now, the next six feet are crucial? Come on. The power cord represents an infinitesimal fraction of the AC current’s total path. Even if the wire in the power cord were so much better, it would have to be stretched all the way back to the power station to make a difference! It’s pure bull on the face of it; no science needed. The fact is that any power cord rated to handle domestic AC voltages and currents is as good as any other. The power cord that came with your amplifier or receiver will give you optimum performance. If you have to buy an extra one, just make sure it’s thick enough in gauge for heavy-duty equipment. If you pay more than a few bucks, you’ve been had. (Besides, as I’ve stated a number times before, your audio circuits don’t know and don’t care what’s on the AC side of the power transformer. What they’re interested in is the DC voltages they need. But that’s engineering science…)

Class T-Amp

09 October, 2006

8-Channel Digital Power Amplifier

AudioDigit Class T-Amp MC8x100

Designed by AudioDigit (www.audiodigit.com) in Italy. Manufactured by Autocostruire di Melani Antonella, Via A. Modigliani 27/B, 51100 Pistoia, Italy. Voice: +39 335 290925. Fax: +39 0573 31018. E-mail: info@autocostruire.com. Web: www.autocostruire.com. AudioDigit MC8x100 eight-channel “digital” power amplifier, 480 euros (c. $610) plus shipping and import duty. Tested sample on loan from manufacturer.

As I have stated before, I’m not really interested anymore in testing parity products (such as, let us say, the 217th multichannel receiver to come on the market) but would greatly prefer to explore new and different, or at least unconventional, designs that point to the future. I was very excited, therefore, to discover on the Internet this strictly 21st-century low-cost amplifier from Italy. It uses special audio-amplifier IC’s manufactured by Tripath Technology Inc. of San Jose, California, which employ a technology Tripath calls Digital Power Processing. DPP-based amplifiers are “Class-T” designs, which are not quite like class D pulse-width-modulation amps but still have similar modulated switching carrier outputs. The claimed benefit is tremendous power efficiency without any tradeoffs in audio quality plus unequaled power/size ratio. I asked for and obtained a review sample of the amplifier, possibly the first Italian MC8x100 to reach the United States.

The Design

The amplifier uses two Tripath TAA4100A four-channel Class-T audio amplifier IC’s, for a total of eight channels. This IC was originally designed for automotive head-unit applications, and pressing it into service to drive domestic high-fidelity speakers is a bit of a stretch, but that was the Italians’ idea. A single toroidal transformer feeds all circuits. The entire eight-channel unit is 17½" wide, which is standard, but only 2" high and 9½" deep. It weighs just a little over 13 pounds. Not even Bob Carver’s famous magnetic field amplifiers of the early 1980s, considered disturbingly small and light by the high-end audiophile press, achieved this kind of size reduction. The amplifier has no controls of any kind, just an on/off switch. There are eight unbalanced RCA-jack inputs and eight speaker connectors of the type that accepts banana plugs, bare wire, or spade lugs. Unfortunately, the binding posts are just a tad too widely spaced to accept dual banana plugs; this is some kind of European hang-up about safety. (They have AC plugs whose dimensions fit the standard dual banana jacks—only an idiot would plug one of these into an amplifier’s output.). Class-T operation isn’t really digital in the sense that 0’s and 1’s are processed in the signal path, but the waveform before the output filter is a complex “digital” waveform (i.e., pulses) of varying frequency. By contrast, the corresponding waveform of a class-D PWM amplifier is fixed in frequency (generally between 100 kHz and 200 kHz). The difference lies in the architecture of the Tripath IC, which we won’t go into here (it involves DSP and “predictive processing,” among other things). The chief benefit is claimed to be power-conversion efficiencies of 80% to more than 90%, while yielding audio quality approaching class A and class AB. (I said, “claimed to be.”)

The Measurements

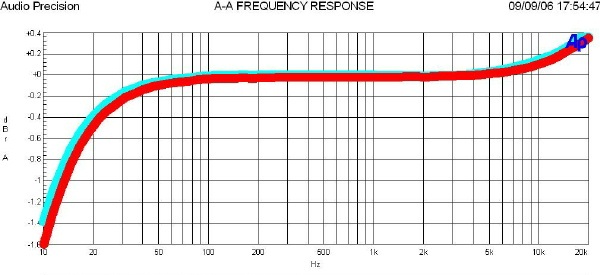

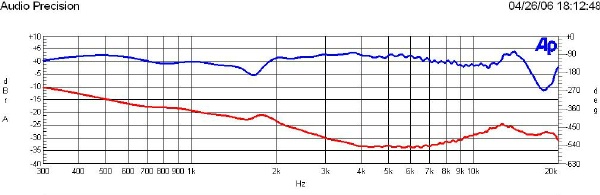

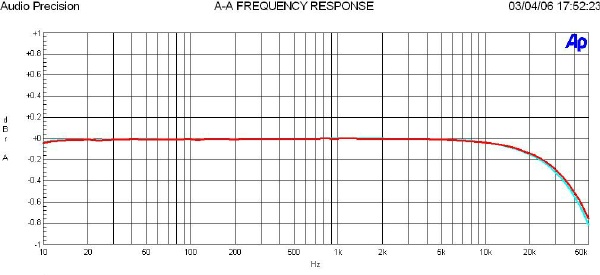

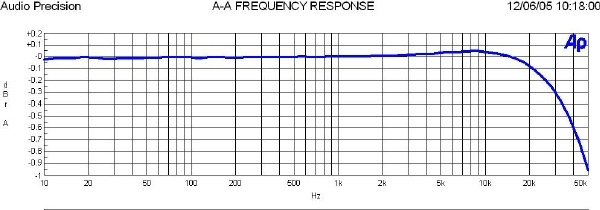

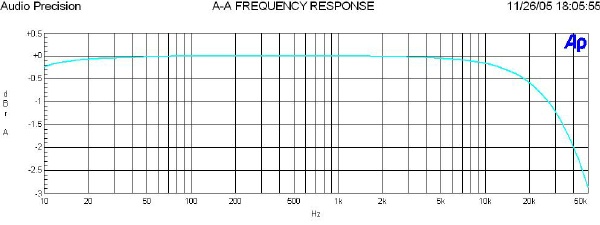

The frequency response of two of the eight channels, at 1 watt into 8Ω, is shown in Fig. 1. The bass rolloff starts at a higher frequency than is normal in standard high-fidelity amplifiers. Down by more than 0.4 dB at 20 Hz is not a very good spec. As for the 0.36 dB rise at 20 kHz, it is almost certainly inaudible but also abnormal. Our analog expectations may be too sanguine in the case of this “digital” amplifier. Let’s not exaggerate, though; this is still a very acceptable frequency response.

Fig. 1: Frequency response of channel 1 (cyan) and channel 5 (red) at 1 watt into 8Ω.

The distortion curves depart significantly from the one in the instruction manual. That one bottoms out at 0.009% (–81 dB) with a 1 kHz input into a 4Ω load and clips at 45 watts, with very high-distortion output available up to 110 watts. My measurement of the same frequency into the same load shows an absolute minimum at –72 dB (0.025%), clipping at 40 watts (in the better of two channels), and maximum available output of 61 watts at sky-high distortion. Big difference. This is basically a low-powered amplifier. (The word I have from Italy is that the power supply in my test sample was set at a lower voltage, for safety reasons, than the one belonging to the amplifier spec’d in the manual.)

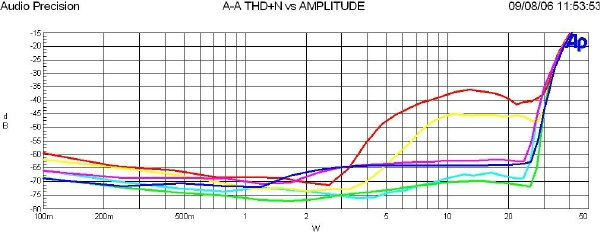

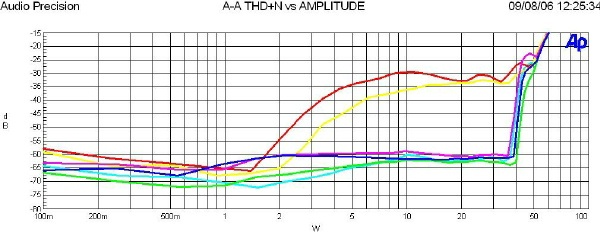

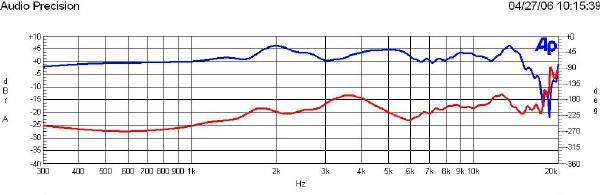

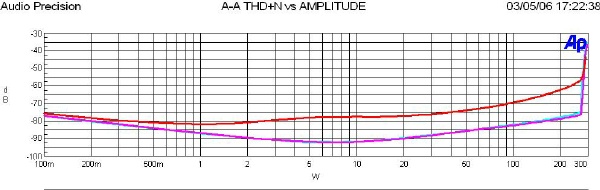

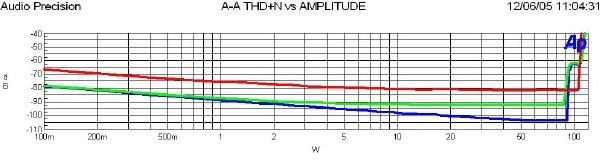

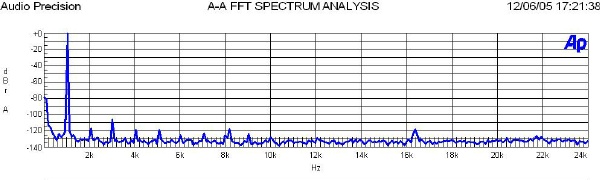

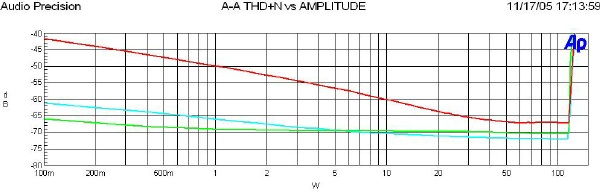

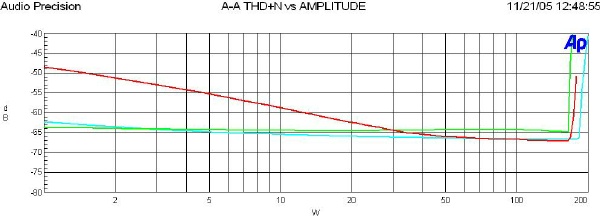

Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 show the THD+N into 8Ω and 4Ω, respectively, at three different frequencies each, for two of the eight channels. Radical filtering above 20 kHz was applied to remove all out-of-band noise, since the out-of-band switching carrier components invariably affect the accuracy of the measurements. That is the reason for the change to 6 kHz from the usual 20 kHz as the highest test frequency; the second harmonic (12 kHz) and third harmonic (18 kHz) are included that way, whereas the use of a 20 kHz fundamental would be meaningless. As can be seen, the curves are pretty much clustered together and stay below –60 dB (0.1%) at all levels, except the 20 Hz curves, which are quite horrible. This amplifier is incapable of genuinely clean 20 Hz output beyond a couple of watts. Maybe the assumption is that a multichannel system driven by the amplifier will have a separately powered subwoofer.

Fig. 2: THD+N vs. power of two channels into 8Ω. Channel 1: 20 Hz (red), 1 kHz (cyan), 6 kHz (magenta). Channel 5: 20 Hz (yellow), 1 kHz (green), 6 kHz (blue).

Fig. 3: THD+N vs. power of two channels into 4Ω. Channel 1: 20 Hz (red), 1 kHz (cyan), 6 kHz (magenta). Channel 5: 20 Hz (yellow), 1 kHz (green), 6 kHz (blue).

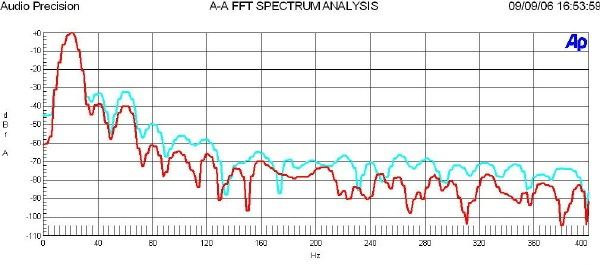

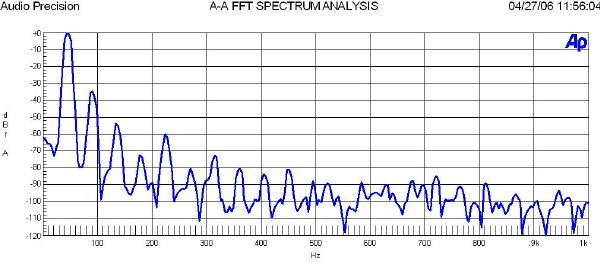

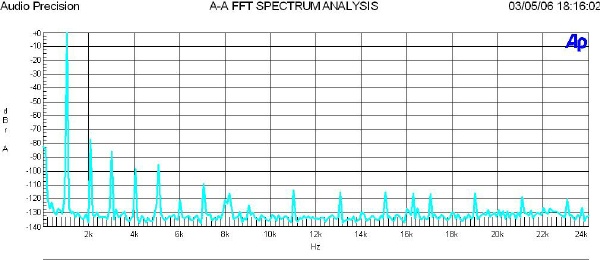

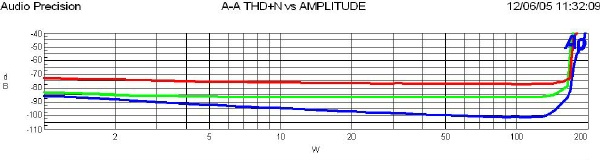

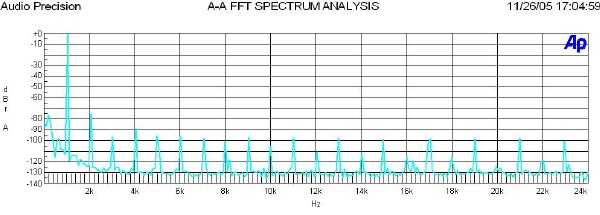

I wanted to investigate the 20 Hz distortion further. Fig. 4 is the FFT spectrum of a 20 Hz tone at 10 watts out, the level of maximum distortion, into a 4Ω load. Two of the eight channels are shown. The curves prove that the high distortion consists largely of second harmonic (40 Hz) and third harmonic (60 Hz), with a little fourth harmonic (80 Hz) thrown in. Nothing mysterious or exotic there; this is absolutely classic low-frequency distortion.

Fig. 4: Spectrum of a 20 Hz tone at 10 watts into 4Ω, two channels (channel 1, cyan; channel 5, red).

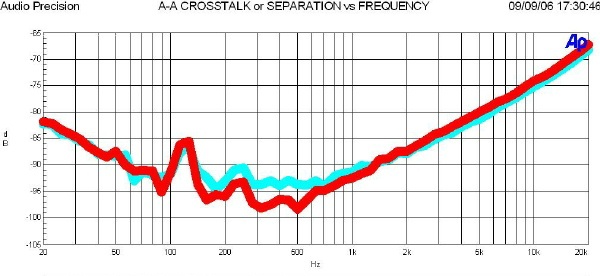

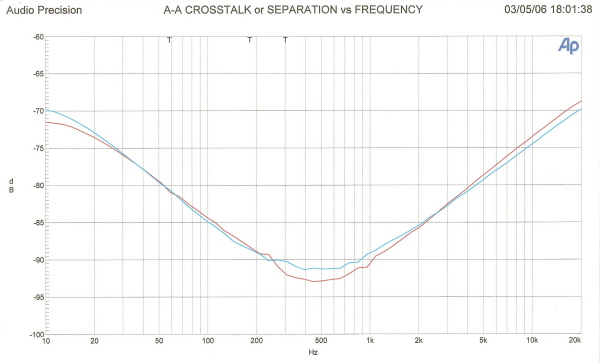

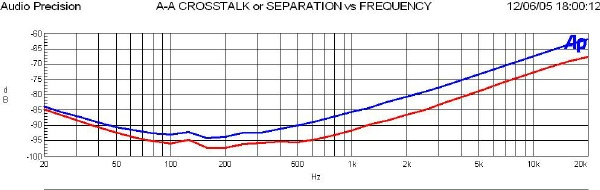

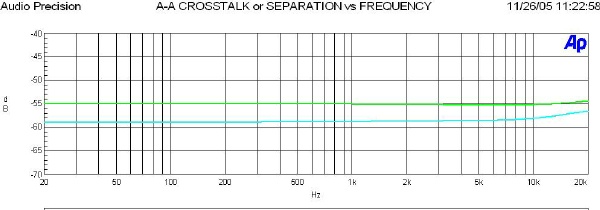

Channel separation, on the other hand, is very good indeed, as shown in Fig. 5. Even at 20 kHz, the crosstalk is of the order of –68 dB, and over most of the audio spectrum it is –80 to –98 dB. That’s right up there with the best. It needs to be pointed out, however, that I measured channels 1 and 5, which are on two separate IC’s. My test setup was wired that way, and I saw no compelling reason to change it. If I had measured two channels on the same IC, the results may not have been quite as impressive.

Fig. 5: Separation between channels 1 and 5 at 1 watt into 8Ω.

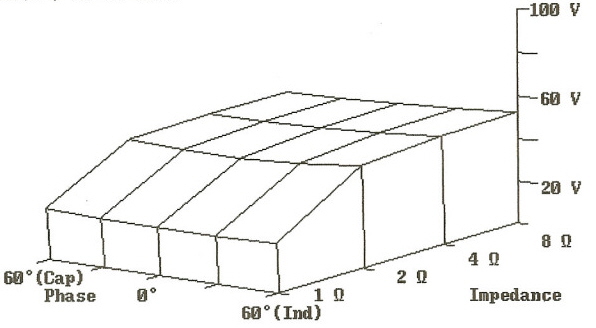

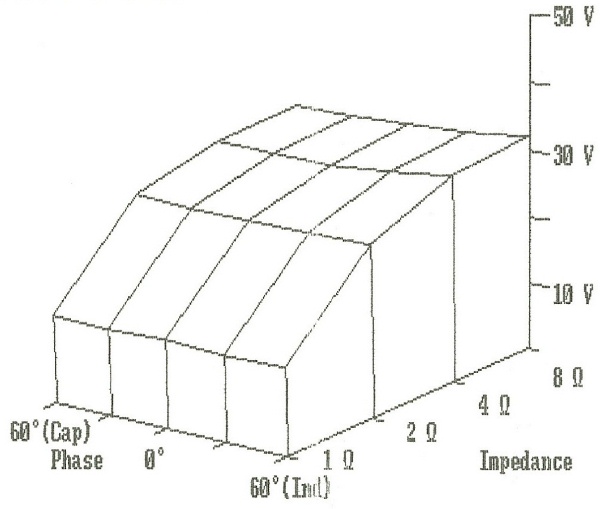

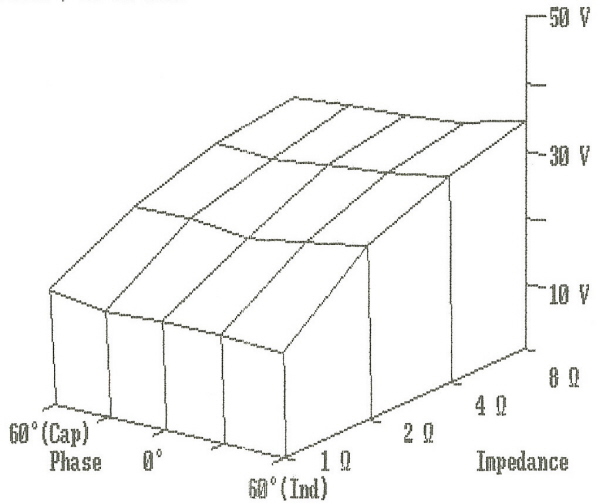

Finally, the PowerCube test was a total bust—not because of bad results but because it could not be performed. As I’ve explained many times before, the PowerCube test measures the ability of an amplifier to drive widely fluctuating load impedances. As far as I know, The Audio Critic is the only American audio journal to publish PowerCube measurements. The instrument for the test is made in Sweden; it produces repeated 1 kHz tone bursts of 20 ms duration into 20 different complex load impedances across the amplifier (magnitudes of 8Ω/4Ω/2Ω/1Ω and phase angles of –60°/–30°/0°/+30°/+60°). The graphic output of the instrument shows the 20 data point connected to form a more or less cubelike polyhedron. The test shows up the differences between otherwise similar amplifiers when it comes to real-world loudspeaker loads rather than just resistances. The AudioDigit amplifier went into protection in the earliest part of the test, on the 3rd of the 20 loads (–60°/2Ω). Obviously, the protection thresholds are set all wrong, in the expectation of 8Ω to 4Ω nonreactive, or mildly reactive, loads only. It is possible that the amplifier could draw a good PowerCube if the protection circuits were set differently.

The Sound

As I have pointed out innumerable times, a properly designed amplifier has no sound of its own. It is impossible for two amplifiers to sound different at matched levels if each has high input impedance, low output impedance, flat frequency response, low distortion, low noise floor, and is not clipped. The MC8x100 is a special case because of its peculiar THD+N vs. power curves, allowing considerable high-distortion output beyond the clipping point. The expectation of some sonic anomalies is therefore not altogether unreasonable. For a quick check, I connected the amplifier to a pair of floor-standing wide-range speakers of decent quality (Sony SS-K90ED’s), with channels 1 and 5 feeding left and right. I thought I heard a few subtle, momentary sounds I didn’t like. An ABX comparison with a conventional amplifier of comparable power would definitely be in order. That takes time, and I want to post this already delayed review forthwith. I’ll do the ABX tests later and append the results here when I am done. (Don’t expect anything revelatory.)

Conclusion

The AudioDigit Class T-Amp MC8x100 is a minor technological tour de force—with warts. I decided not to use it between the electronic crossover and the eight drivers of my pair of Linkwitz Lab “Orion” speakers, which was my original plan before I did the measurements. There just isn’t enough power before clipping, and after clipping the bizarrely available power appears to be unacceptable because of high distortion. Too bad—I would have liked to tell the high-end fanatics that I am using a really cheap amplifier to drive a state-of-the-art loudspeaker. The amplifier may still be perfectly adequate in a surround-sound system using conventional speakers, but we’d better wait for the ABX tests to confirm that.

PS: No ABX Test

Well, I set up an ABX test. Very carefully. (The identity of the other amplifier is at this point irrelevant, as you will see.) When I switched on the AudioDigit amplifier, it started to smoke and smell, and blew its power-supply fuse. Removing the cover, I identified the cluster of power-supply capacitors as the culprit. They smelled smoky; the rest of the amplifier did not. I think what happened was that my line voltage was a little high that afternoon, and the amplifier could not take the turn-on surge. Of course, one or more capacitors could have been faulty to begin with. Maybe it was pure luck that the measurements could be completed. The rest of the equipment plugged into the same power strip—and that includes the other amplifier—did not bat an eyelash. Nor have I had a similar problem with any piece of gear in the 18 years I have lived in my house. Draw your own conclusions. The amplifier is going back to Italy. Maybe they’ll send me an improved version. I still think it’s a very intriguing design that breaks with the past and looks ahead.

NXT Loudspeakers

09 August, 2006

A Note on NXT Distributed Mode Loudspeakers

This was an attempt to investigate the high-fidelity possibilities of a radically new and different transducer technology.

NXT is a fairly young but rather large company based in Huntingdon, England. They are responsible for the development of the Distributed Mode Loudspeaker (DML), which is a flat-panel transducer that can assume innumerable different shapes and forms, both opaque and transparent, and is not based on the piston concept but on bending-wave physics. A DML panel vibrates in a large number of modes instead of moving back and forth as a rigid piston-like unit. I have never seen a formal mathematical analysis of the basic design, but there are literally hundreds of products out there, large and small, using the NXT patents, from “talking” TV screens to cheap little surround-sound satellites. Everything except high-end audio—and I wondered why. (Actually, I witnessed a CES demo of a high-endish prototype a few years ago, but it never flew.)

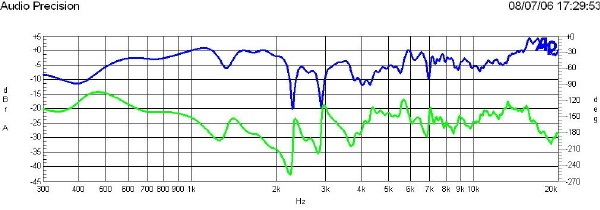

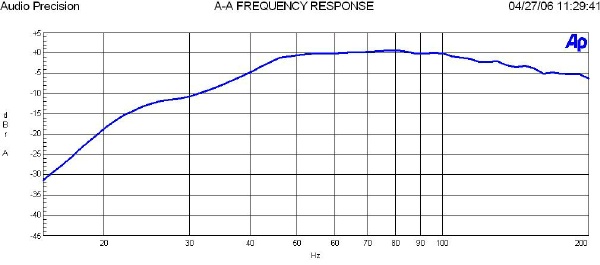

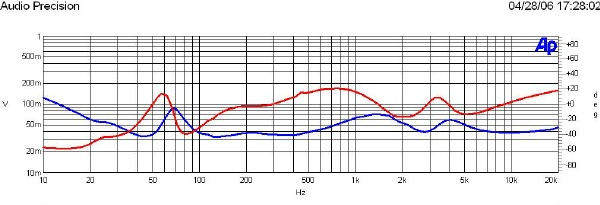

I managed to get my hands on a two-foot by one-half-foot transparent NXT panel, which had been part of a discontinued mass-brand compact music system. I know that this panel does not represent the state of the art in DML technology, but it was intended to reproduce music and therefore promised to give me a minimal indication of the hi-fi possibilities of the DML concept. I connected it to my bench amplifier (no EQ, as there may have been in the commercial system) and set it up to run a frequency-response curve with the MLS (quasi-anechoic) method. The result is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Frequency response at 1 meter on axis (amplitude blue, phase green).

As can be painfully seen, the response is horrible—so horrible, in fact, that I do not believe it. It is possible that the bending-wave/multimodal sound propagation cannot be accurately measured with the MLS method. I am just speculating because, as I said, I have not seen a formal analysis of the system. Maybe some kind of averaging measurement at a large number of points would be more valid. I just don’t know. My reluctant conclusion, tentative as it is at this juncture, has to be that the hi-fi potential of the DML concept is extremely limited and that the absence of high-end applications is inevitable. I hope to change my mind if and when contrary evidence becomes available to me.

CDs & SACDs Again

18 July, 2006

Back to CD/SACD Reviews

As our regular readers know, I am neither a professional musician nor a tweako audio cultist. You won’t find either one of those perspectives here. I just listen to CDs (mostly classical), look at and listen to DVDs (mostly opera), and pick a few interesting ones for my brief and modestly offered reviews here. The assumption is that music-loving audiophiles and audio-savvy music lovers will find at least some of my stuff worth reading because I try to engage them on their level.

CD from/by The Fry Street Quartet

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in A Major, Op. 18, No. 5; String Quartet in A Minor, Op. 132. Igor Stravinsky: Three Pieces for String Quartet (1914). Ned Rorem: String Quartet No. 4 (1994). J. Mark Scearce: String Quartet 1o (Y2K). The Fry Street Quartet (Jessica Guideri, violin; Rebecca McFaul, violin; Russell Fallstad, viola; Anne Francis, cello). FSQCD3 (2 CD/SACDs, 2004).

If this release had come from Sony BMG or Deutsche Grammophon or EMI, there would have been a lot of rave reviews by now. But since it was self-published by The Fry Street Quartet, it attracted no attention from music critics, at least the critics I keep track of. Too bad, because in my humble opinion (IMHO is the oh-so-hip Internet shorthand) these discs are both an artistic and an audio event. The Fry Street Quartet is right up there with the best, both technically and musically, and Ray Kimber’s IsoMike technique, used here for the first time in a full-length classical release, appears to be a significant step up from conventional miking approaches. I say that knowing full well that Ray Kimber’s main business is selling obscenely overpriced fantasy cables to gullible audio neurotics. His recording of a string quartet, on the other hand, is simply the best I’ve ever heard, surpassing even the best work of Max Wilcox and John Eargle. The sound has a lifelike presence, effortless fullness, and natural resonance unequaled in my experience. IsoMike (“Isolated Microphones”) is a system that separates the recording microphones by means of huge, oddly shaped baffles of complex mechanical design (see www.isomike.com). How and why this works need not be discussed here, but the resulting acoustic detail is uncanny. The DSD recording uses 4.0 channels, but I liked the plain stereo layer best through my Linkwitz Lab “Orion” speakers. The rear channels contribute relatively little. As for the music, the Beethoven Op. 132 is one of the pinnacles of Western art, a desert-island Top Twenty, completely dwarfing the quite wonderful but very much earlier Op. 18, No. 5; the Stravinsky piece is a short exercise in Sacre-like rhythms and sonorities, mighty stylish; the Rorem quartet is a highly listenable romantic/acerbic “Pictures at an Exhibition,” this time anent ten paintings by Picasso; the Scearce quartet is reminiscent of Bartók without the latter’s originality and loftiness of purpose. Throughout, the ensemble playing, phrasing, and tone of the Fry Street Quartet are on the highest professional level, in a league with the big-name quartets of the world. That the FSQ is three quarters female has an effect on their style (again, IMHO); their playing is simply beautiful rather than pointed. I am fully aware that this exposes me to the wrath of feminists who don’t believe in vive la différence! At any rate, this recording is a major sleeper.

CD from Harmonia Mundi

Frédéric Chopin: The Complete Waltzes. Alexandre Tharaud, piano. HMC 901927 (recorded 2005, released 2006).

I knew it. If anyone was going to rival the Dinu Lipatti 1950 and Artur Rubinstein 1963 recordings of the Chopin waltzes, it would be Alexandre Tharaud. He is the young French pianist of impeccable taste and superior intellect whose Ravel recording I raved about a while ago and whose name ought to be a lot more famous than it is. (Not that great Ravel playing automatically implies great Chopin—it did not, for example, in the case of the fabulous Ravel interpreter Walter Gieseking—but what we have here is the French Connection!) On this CD Tharaud presents all 19 of the waltzes, including the 6 posthumous opuses, in a nonchronological sequence that constitutes a neatly balanced one-hour program. His technical fluency, his carefully judged rubato, his elegant yet often passionate phrasing, his dynamics are all on a level that, to my ear, threatens to set a new standard. The Grande valse brillante, Op. 34, No. 1, had me wildly applauding the CD player! I have a theory that the very best efforts of the present, in any field, inevitably surpass the best efforts of the past. Roger Bannister ran the mile faster than Paavo Nurmi, and Hicham El Guerrouj runs it a lot faster than Roger Bannister. Time marches on; techniques are refined; benchmarks are reevaluated; nothing is sacred. I think that Tharaud probably has a better intellectual grasp of what the Chopin waltzes are all about than previous generations of pianists. Sue me if I’m wrong. As for the audio, the sound of the piano is as good as it gets; the correct setting of the volume control brings the Steinway D right into your room. In every way, a triumph!

CD from Naxos

W. A. Mozart: Eine kleine Nachtmusik (Serenade in G Major), K. 525; Serenata notturna, K. 239; Divertimento in F Major (Lodron Night Music No. 1), K. 247. Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Petter Sundkvist, conductor. 8.557023 (recorded 2004, released 2006).

“Eenie kleenie” used to be everybody’s introduction to classical music, including mine. It is hackneyed, yes, but still a gem, full of unforgettable melodies and possessing great formal structure. Amazingly, I’ve never had the opportunity to write about it; this is the first time. This version is exactly right, played by a double or at most a triple string quartet plus one contrabass; the piece sounds bloated and unnatural when the whole string section of a huge symphony orchestra plays it. Basic Mozart doesn’t require great virtuosity to be played elegantly, just some taste, musicality, and an understanding of style. The Swedish Chamber Orchestra has all those qualities in abundance. You don’t need a better performance, even if better ones exist (after all, the competition is huge). The gorgeous stereo recording reinforces that conclusion, presenting a thoroughly palpable soundstage and superb string sonorities. The other two serenades fall short of immortality, being much earlier Mozart, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t utterly delightful. The man was, from day one, genetically incapable of composing mediocre music. K. 239 has some startlingly colorful instrumentation in the last movement, with flashy timpani rolls. K. 247 has some lovely passages for two horns. When he was not being original, Mozart was merely beautiful. His music is sometimes transcendently great, sometimes just routinely wonderful, never negligible.

SACDs from Ondine

Bohuslav Martinu: Memorial to Lidice, H. 296. Gideon Klein: Partita for Strings (arr. Saudek). Béla Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra, Sz. 116. The Philadelphia Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach, conductor. ODE 1072-5 (2005).

The great Philadelphia Orchestra, my special favorite, had to go to a Finnish label to have its new recordings published and marketed—a sign of the times. No special recording sessions, either; all releases are edited from live recordings of scheduled concerts in Verizon Hall. The centerpiece of this CD is the Bartók, which at 63 years old is—believe it or not—the youngest composition to become a regular repertory item of every major orchestra in the world. Nothing composed even 50 years ago is played as regularly, over and over again. Amazing. The Bartók, Martinu, and Klein pieces were all composed within a few months of each other, in 1943-44, which appears to be the “album concept” here (as if we needed one). The latter two did not become repertory items—I give you three guesses why. They’re moderately interesting and beautifully performed by Eschenbach, and that’s that. The Concerto is of course a masterpiece, fully deserving its fame, with superior performances under every major conductor of the 20th century in the catalog. Reiner/Chicago 1955 is still considered a benchmark; it combines authenticity, intensity, elegance, virtuosity, and great sound by Lew Layton—all in all, hard to beat. Eschenbach presents a 21st-century performance, in which all the traditionally emphasized Bartókian savagery has been subsumed under a more comprehensive scheme of balance, structure, transparency, and sheer beauty. It becomes clear that the music is no longer “modern.” The exquisite Philadelphia woodwinds, the golden brass, the plush strings seem to imply that a gut-wrenching approach would be downright vulgar. I find this level of orchestral playing utterly disarming—“do anything you want” is my emotional reaction. Eschenbach totally sells me gorgeous Bartók over exciting Bartók. Such is the power of a stupendous orchestra under a strong-willed conductor. Not that certain passages are lacking in excitement; the last-movement presto, for example, is taken at breakneck speed, almost flirting with danger. The recorded sound is also magnificent; the tunable hall’s resonance chambers are in finer adjustment than in the Sawallisch/Schumann recordings I reviewed some time ago, and everything is in superb balance. That goes for the stereo layer as well as the SACD 5.1-channel layer, which for once provides excellent localization and envelopment. You should own more than one recording of this piece, and this should be one of them.

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.5 in E Minor, Op. 64; The Seasons, Op. 37b (January-June). The Philadelphia Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach, conductor & piano (in The Seasons). ODE 1076-5 (recorded 2005, released 2006).

I looked forward to this release because in March 2006 I heard a very beautiful performance of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony at the Kimmel Center by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eschenbach. Their recording of the Fifth is a disappointment. The orchestral playing is magnificent, as usual, but Eschenbach’s concept of the symphony departs radically from my musical expectations. A tight, sinewy, fairly swift performance, as in Mravinsky’s unforgettable 1960 recording on Deutsche Grammophon, still preserves all the romanticism of the music because it’s built into the score; indeed, the romantic phrases remain more coherent if you don’t slow them down but get on with it. Eschenbach lingers meltingly over every lovely phrase, producing an almost whiny effect. His performance is 50½ minutes long as against Mravinsky’s 43! Admittedly, there’s more than one way to skin a cat, especially when it comes to Tchaikovsky, but Eschenbach’s way is too much for me. (I’m reminded of the great—and notorious—Willem Mengelberg’s precept: “In Tchaikovsky, everysing a leettle exagéré.”) The relatively lightweight Seasons, for piano solo, is tossed off prettily and unpretentiously by Eschenbach, but why play only the first 6 of the 12 pieces? Because that’s all that fits on the CD after the symphony? Come on! As for the recorded sound, the stereo layer is not quite as precisely delineated and transparent as in the Bartók recording above, with somewhat attenuated highs and slightly congealed climaxes. The balance engineer was not the same on an otherwise identical recording team, which could be the reason. In this case I actually prefer the SACD multichannel layer through my Waveform home-theater system because the climaxes are cleaner, and both the localization and envelopment are excellent. (Can’t each layer be totally optimized?) I would rate this whole effort on the low end of the scale for the three Phidelphia/Verizon Hall recordings released so far.

Canton Loudspeaker

07 May, 2006

Floorstanding 3-Way Loudspeaker System

Canton Vento 809 DC

Canton Electronics Corp., 1723 Adams Street NE, Minneapolis, MN 55413. Voice: (612) 706-9250. Fax: (612) 706-9255. E-mail: info@cantonusa.com. Web: www.cantonusa.com. Vento 809 DC floorstanding 3-way loudspeaker system, $5000.00 the pair. Tested samples on loan from manufacturer.

Canton is not a Chinese brand, the name notwithstanding. The speakers are made by the Canton Elektronik company in Germany and distributed in this country by the company’s U.S. affiliate. Even the earliest print issues of The Audio Critic, back in 1977, contained some Canton reviews, but the Vento Series is relatively new.

As readers of this Web ’zine know, I am not very interested in “monkey coffins” anymore (a monkey coffin being a rectangular box with passively crossed-over forward-firing drivers), and the Vento 809 is still basically a monkey coffin despite its gracefully rearward-curving sides. So why am I reviewing it? Mainly because it’s roughly the same size at the same price with the same number of drivers as my Linkwitz Lab “Orion” reference speaker, and by contrast it’s quite conventional in engineering. A valid comparison of good standard vs. maverick design.

The Design

The Vento 809 is a little under four feet high and takes up less than a square foot of floor space. Its horizontal cross section is two thirds of an ellipse with the tip chopped off. The bass-reflex enclosure houses two 8" aluminum-cone woofers, a 7" aluminum-cone midrange, and a 1" aluminum-manganese dome tweeter. The crossover frequencies are 250 Hz and 3 kHz. The cabinet, made with a multilayer lamination process, is exceptionally solid and acoustically dead. Two pairs of terminals are provided for biamplification, which has certain advantages, or biwiring, which is utter nonsense. Unfortunately, the manual does not make that distinction—the tweako/cultist tradition is honored.

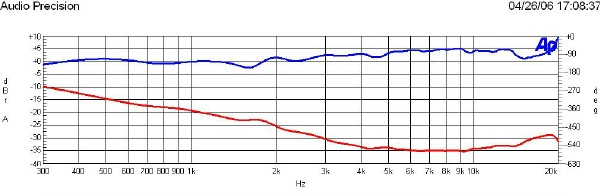

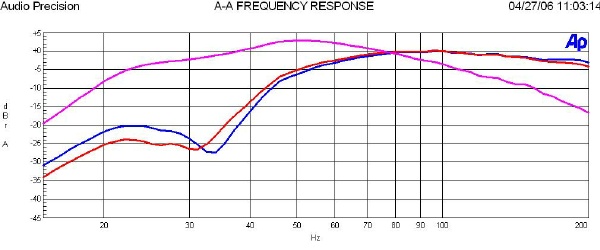

The Measurements

I took three quasi-anechoic (MLS) frequency-response curves at a 1-meter distance: on the tweeter axis (Fig. 1), 45° off axis horizontally (Fig. 2), and 45° off axis vertically (Fig. 3). As I have pointed out before, quasi-anechoic measurements with the Maximum Length Sequence technique are not as reliable and accurate as measurements made in an anechoic chamber or outdoors under windless conditions. The former, however, are a lot faster and more convenient, and they indicate the overall trends more than adequately for our purposes. What are those trends in the case of the Vento 809? Not good, I’m afraid. The three curves clearly show that the power response into the room is rather heavily skewed toward the higher frequencies, from about 2 kHz on up. Below that frequency the response is reasonably flat; above it there’s a lot more output no matter where the measurement microphone is placed. This is not a peak but an excess of energy distributed over several octaves. If the only problem is that the tweeter is set too high (“I vant more brilliantz, Helmut”), it’s easily remediable. As it is, it’s highly audible (see below).

Fig. 1: Frequency response (amplitude blue, phase red) at 1 meter on tweeter axis.

Fig. 2: Frequency response (amplitude blue, phase red) at 1 meter 45° off axis horizontally.

Fig. 3: Frequency response (amplitude blue, phase red) at 1 meter 45° off axis vertically.

The bass response can be accurately measured with the nearfield technique (originally developed by our sometime contributor Don Keele). Fig. 4 shows the nearfield response of the two woofers and the bass-reflex vent. The curves are highly accurate from 100 Hz on down. Fig. 5 shows the summed nearfield curve, taken at a point experimentally determined to yield the flattest and deepest response. It appears that the box is very loosely tuned to around 32 or 33 Hz and that the –3 dB frequency (f3) of the summed response is 42 Hz. The –6 dB frequency, generally considered the limit of bass response, is 38 Hz. I expected deeper bass from a $5K-a-pair loudspeaker.

Fig. 4: Nearfield frequency response of the two woofers (blue and red) and the vent (magenta).

Fig. 5: Overall nearfield bass response.

Fig. 6 shows the distortion products of a 45 Hz tone played at a 1-meter SPL of 96 dB. That’s the lowest frequency within the ±1 dB flat response of the speaker, and 96 dB is about as loud as it gets that low in the bass. The 2nd harmonic (doubling) distortion is –35 dB (1.78%), the 3rd harmonic –53 dB (0.22%), the 4th harmonic –72 dB (0.025%), the 5th harmonic –60 dB (0.1%), the 6th harmonic –73 dB (0.022%), the rest totally negligible. I would call that an excellent result, confirming the quality of the 8" drivers. Generally, bass distortion is by far greater than midrange or treble distortion, so this is the only THD measurement I took.

Fig. 6: Nearfield spectrum of a 45 Hz tone at a 1-meter SPL of 96 dB.

The impedance of the Vento 809 is shown in Fig. 7. (Ignore the curves below 35 Hz; they are irrelevant.) The magnitude dips as low as 3.4Ω at 45 Hz and 130 Hz, and peaks to 9Ω at 67 Hz and to 7.1Ω at 1.35 kHz. The phase fluctuates between –35° and +21°. Any half decent amplifier can happily drive a speaker with that impedance.

Fig. 7: Impedance magnitude (blue) and phase (red).

The Sound

Speakers that measure poorly but sound great exist only within the pages of Stereophile. The Vento 809’s excessive output of high frequencies above 2 kHz is not only measurable but readily audible. If a recording is on the bright side to begin with, its reproduction through the Vento 809 will be downright unpleasant. If it is a well-balanced recording, it will merely sound overbright. The effect is most obvious on axis but is still clearly perceptible no matter where you sit. By contrast, the Linkwitz Lab “Orion” is gorgeously listenable on recordings with a wide range of brightness; they will simply be reproduced with varying degrees of presence. (Of course, the Orion doesn’t really “exist” in the commercial sense.)

As I suggested above, the fault may be only skin-deep; perhaps the tweeter just needs a little more padding. The speaker appears to be well-engineered overall; the bass is on the light side but the sound is quite transparent and spatially detailed. I really doubt if the engineers are responsible for the exaggerated high frequencies; they know better. Probably some higher-up decision maker wanted that sound for marketing reasons, thinking it will sell better. (Jawohl, Herr Generaldirektor!) He overlooked the fact that the Vento 809 is not a kitchen radio. I seem to remember that the Canton speakers I reviewed in 1977 were also overbright. Corporate culture?

Pad out that tweeter, Ingenieure, and send the speaker back to me. (Fat chance…) I think I’ll like it then.

Interviewing the Ed.

13 April, 2006

Your Editor, Revealed

An Unprecedented Interview

Editor’s Note: The following interview was conceived, produced, and edited by a longtime subscriber to The Audio Critic who wishes to remain anonymous. It was conducted by e-mail over a period of a few weeks in March/April 2006. The questions were entirely the interviewer’s choice; your Editor merely answered them as best he could.

In 1977 I came across an advertisement within the pages of the erstwhile Audio magazine, an advertisement for a new audio publication promising reviews of high-end gear based on a kind of technical competence not found elsewhere. The price seemed high, but who could resist? I sent my check never expecting that, almost 30 years later, I’d still be reading. Over the years I purchased equipment based upon the Editor’s recommendations, never dissatisfied. And over the years, although the format changed, editorial standards set forth for all to read in Volume 1, Number 1 were maintained. Equipment reviews were factual, and presented with a unique and literate flair not found elsewhere. As time passed I often wondered about the man responsible for The Audio Critic. I knew what he thought about audio but I never really knew much about him as an individual—that is, his background and the thinking leading him to publish The Audio Critic. In any case, my own thinking evolved as I read the Editor’s writing, and the writings of his contributors.

After reading his musings on the audio scene as he reflected upon what it all meant, especially in anticipation of his 80th birthday, I decided to track him down. My idea was that, to commemorate his birthday, he ought to put down in his own words his personal story for the benefit of his readers. Once I’d caught up with him he told me he was, frankly, not interested. His view was that The Audio Critic’s purpose was to highlight the audio scene. It was about music, the equipment we use, and the technology. It was not about him. Nevertheless, I was persistent—more persistent than I had a right to be—and he finally decided to give it a go. Thus it is, after all these years, we finally have our Editor, Peter Aczel, the man, in his own words, and within his own pages.

Finally, a brief disclaimer regarding what you are about to read: I am no technologist, nor am I associated with anything or anyone related to the audio industry. I am simply a longtime subscriber. The questions are my own, and the Editor had no input or foreknowledge about what I asked. However, he candidly answered whatever I put to him. The questions cover a variety of topics and, while they may not be questions you would ask, they were questions that, for me, I always wanted to ask.

Q. Some time ago you published a very funny cartoon that, in many ways, captured the irony of the hi-fi scene. It featured an audiophile with a very expensive “high-end tweako” system demonstrating it to a music-loving acquaintance. After the listening session ended, the gearhead wanted to know his friend’s opinion. The music lover thought a minute, then replied, “He conducts it a lot faster than Bernstein, doesn’t he?” Since oftentimes the music seems to take a back seat to the equipment, but since the music is really what our hobby is all about, I thought it might be best to begin by asking you about your early musical influences.

A. When I was eight years old, in Hungary, my mother decided I should have piano lessons. She sent me to a minor-league concert-pianist lady (the mother of one of my elementary-school classmates, actually), who turned out to be an unpleasant and unpersuasive teacher. I hated every minute of it. I was then switched to an amateur pianist lady, who was on the other hand a wonderful teacher. She had me playing simple pieces by Schumann and Bartók (this was in the mid-’30s!) in no time. She even took me to a children’s concert where a women’s chamber orchestra played Eine kleine Nachtmusik and Béla Bartók himself played some of his Hungarian folk-song arrangements on the piano. No big deal, just one of the two greatest composers of the 20th century noodling around on the piano to entertain the kids. (The other, Igor Stravinsky, was I am sure too stuck-up to have done the same. Besides, Bartók was also a world-class pianist; Stravinsky wasn’t.) By then I was hooked on music for life. By the time I left Hungary for the USA at the age of 13, I had been to the opera numerous times and tried to catch every classical-music broadcast on the radio. In the USA I started to collect 78-rpm shellac records, sporadically paid for out of my very meager allowance and played on an absolutely miserable portable phonograph with steel needles. At 16, my favorites were Wagner’s “Magic Fire” (Philadelphia/Stokowski) and Beethoven’s Op. 132 string quartet (Budapest Quartet). From there on, my musical development was more or less inevitable.

Today, a child not only attending the opera but enjoying it, is a bit out of the ordinary. Was this kind of “classical education” typical at the time? Also, were there any particular performances that made a lasting impression on you?

It wasn’t altogether typical, but there were a lot more kids who enjoyed classical music than in today’s hip-hop generation in America. Among the performances I remember, there was a Rigoletto with the almost forgotten world-class tenor Kálmán Pataky singing the Duke, and of course the Béla Bartók concert I have already talked about.

You came to the US in the late ’30s? Was this due to the political situation in Europe?

Yes and no. My father was the managing editor of a liberal daily newspaper in Budapest (not excessively left-wing, actually). When Hitler occupied Austria in 1938, he said, “This is it, it’s all over for Europe.” We had a good life and could have stayed there for a number of years, but he decided, with a good deal of prescience, to take the family to the United States, where he had sisters living since the 1920s. In 1944, after the Germans had occupied an insufficiently cooperative Hungary, the Hungarian Nazi thugs had free reign and turned the country into a nightmare. The entire staff of my father’s not-very-left-wing newspaper, without exception, ended up in a concentration camp. It wasn’t a death camp, and they all came back after the war, but most of them were walking skeletons. So my father ended up having been right, and how!

Most audiophiles recall the first time they heard hi-fi sound. It is usually a defining moment and one that sets in motion a desire to pursue the hobby. Can you tell us about the first time you experienced high fidelity sound, and what impression this had on you?

It was in 1948, when I was 22. I went to an electronics show in New York and heard an early Magnecord tape recorder play a live recording of the Air Force Band through an Altec Lansing theater speaker. I was blown away. The sound had real-life dynamics and harmonic detail. I hadn’t thought until then that this was possible. Again, the consequences were inevitable.

What about your first stereo system?

I go much further back than the dawn of stereo. My first mono system was assembled in 1948 (shortly after the New York show experience) and consisted of an 8-inch Altec Lansing full-range speaker in a bass-reflex enclosure, a 10-watt all-triode amplifier designed by Consumer Research (the now-extinct rival of Consumers Union), a Meissner FM tuner (ever heard of it?), and a cheap record changer with an Astatic crystal pickup. I tried to figure out whether the dimensions of the ready-made bass-reflex enclosure were correct for the Altec Lansing driver; they seemed to be close according to the rudimentary Novak formulas (Thiele-Small came much later).

As a kid, were you an electronic tinkerer? Did you take things apart in order to see how they worked?

No, I was into chemistry. An 11-year old kid could walk into a pharmacy in those days (at least in Hungary) and purchase concentrated sulfuric acid or pure sodium hydroxide. If my mother had known what I was concocting in the bathroom, she would have had a fit.

Early on it seems that you were interested in the art (or should I say, science) of speaker design theory, and from your writing it’s evident that you’ve a pretty solid grasp of electronic theory. Are you self-taught? Did you learn all of this on your own, in your “spare time,” as they say?

Not quite. At Columbia College of Columbia University (Class of ’49) I majored in physics and mathematics, getting a good foundation in the scientific fundamentals. The specifically EE-oriented information I absorbed gradually on my own, prompted mainly by my interest in audio, but I knew from the start what an ohm and a volt and an ampere were, and I even had an adequate entry-level knowledge of calculus. The finer points of speaker design I became aware of only after getting involved with Ohm.

How did you become associated with Ohm Acoustics?

A self-taught audio engineer by the name of Marty Gersten had been fired by Rectilinear (a loudspeaker company that no longer exists) and needed a job. I was doing Rectilinear's advertising (on the side, not through my ad agency) and knew Marty from there. He had some interesting ideas about speaker design and persuaded me to make a small investment in a new loudspeaker company, along with a number of other partners. It was I who actually named the company.

You later reviewed the Ohm F. At the beginning of the review you stated up front that you had been, but were no longer, associated with the company. You came down pretty hard on the speaker, even though you admitted respect for the Walsh design theory. From a personal standpoint, was it difficult to show the kind of candor found in your review (that is, your highlighting all the speaker’s shortcomings), given your prior professional association with the company?

Not at all. By the time I was divorced from the company it was entirely owned by Tech HiFi, and the divorce had been rather unpleasant, although in the end I got a reasonably fair deal. Years later, when I did the review, I had no emotional ties to the company; furthermore, the Ohm F design ended up with huge compromises I had nothing to with.

When The Audio Critic arrived, there were three widely circulated audio magazines—Stereo Review, High Fidelity, and, to a lesser extent circulationwise, Audio. Of the limited distribution “undergrounds,” Gordon Holt published Stereophile, and Harry Pearson had founded The Absolute Sound. The contrast between the first group and the second was quite pronounced. When did you first get the idea that a new publication was necessary?

A friend suggested it. Underground audio journalism was in the air, an emerging phenomenon, and the existing undergrounds did seem a little bit fantaisiste. I was fed up with my career as an ad agency creative director, so I tested the waters. I ran a half-column ad in Audio with the headline “The Audio Critic is coming!” The ad promised equipment reviews based on measurements, not opinions. I got 1200 advance subscriptions before anyone saw the first issue. I quit my job and retired from Madison Avenue.

A friend first suggested you start The Audio Critic, and this seemed to you like a good idea? Forgive me if your answer sounds like you are glossing a bit. Surely there must have been more to your decision by way of background than simply picking up on a friend’s suggestion? After all, going from Madison Avenue to audio equipment reviewing is not a casual career decision.

I was fed up with Madison Avenue. I was looking for an excuse to quit. Initially I thought I would do The Audio Critic on the side, but when those 1200 subscriptions came in without anyone having even seen the first issue, I decided to take the plunge. At first it was exhilarating, but then in the 1980s, when the whole audio scene had slowed down and not much was happening, I actually tried to get back to Madison Avenue. I went to see my former boss, the great adman Ed McCabe (of Scali, McCabe, Sloves, later absorbed by the ever-larger corporate structures of the ad world), who said he considered me a very good copywriter but the business had changed and good writers were no longer needed. (He was right, too; look at today’s TV commercials). All in all, I think I had a better life sticking with The Audio Critic.

In your first issue you began a review of two dozen preamps. Most were paid for out of pocket—your pocket. How long did it take to actually get all of this gear together, and how long was it from your initial purchase until you could get the first issue out the door?

I started assembling the preamps in October 1976, and the first issue was mailed February 1, 1977.

What the hell did you do with all those preamps once you were finished with them?

I had an arrangement with a Long Island hi-fi store. I bought all the preamps from them, and they committed themselves to buying them all back at a reduced price. The spread wasn’t particularly great, but when multiplied by 22 it was still very good business for them.

After the public had digested the first few issues of The Audio Critic, you had pretty much polarized the audio scene. It seemed as if people either loved what you were doing, or they reacted with a kind of visceral animosity towards you, personally. Did you expect this kind of reaction, or were you surprised?

I always knew that audiophiles were emotionally challenged, but the intensity of their reactions did surprise me. After all, it wasn’t about the honor of their wives or the talent of their children or their next salary raise, but a freakin’ preamp, for crying out loud.

When it comes to hi-fi, most people usually think only of the end product—that is, how the music sounds in one’s living room. However, it was clear from early on that your interest was not merely one of end results but the entire recording chain. For instance, from day one you featured Max Wilcox as an associate editor. When did you first become interested in the back-end process, as opposed to the mere recreation of the recorded event in a domestic setting?

I was always aware of differences in recording technique, even in the shellac days, but did not give them too much thought until I had fairly high-resolution playback systems. It was a gradual process. Actually, it is only now, listening to my Linkwitz Lab “Orion” speakers, that I realize just how much better Lewis Layton was in the 1950s than nearly all recording engineers with their fancy equipment in the 21st century. It’s kind of depressing. By the way, I think the three greatest recordists of the modern audio era were Lew Layton, John Eargle, and Max Wilcox. There is a serious quality difference between their recordings and just about all others, to this very day. Some of the others are pretty good, but as Voltaire said, the best is the enemy of the good.

It is interesting that you quote Voltaire, a figure from the French Enlightenment, and a thinker who reacted strongly against the old scholasticism. If we view scholastic thinking as a way of holding up prevailing ideas based on faith, then we can contrast this with a new method where scientific thinking displaces a more naïve view of what has come before. The key, I think, is in method. You were always interested in formulating a precise methodological approach to reviewing equipment. In 1977 you discussed in print how listening tests should be conducted. For example, you wrote, “...you can’t compare the sound of something like, say, the Mark Levinson JC-2 and the DB Systems preamp by testing one unit in August and the other in November.” You then went on to discuss A/B testing in detail. Would it be wrong to conclude that, over the years, methodology has been your overriding concern in audio reviewing?

Audio reviewing comes down to method and not much else. Audio is in itself a method, a means to an end (which is reproduced sound in the listening room), and to evaluate a method without a methodology is an absurdity. What audio journalists without a methodology are engaged in is mere opining, not reviewing or evaluating. (Stereophile is a special case because they have a methodology but exhibit a total disconnect between their methods and their opinions.) I must add that all this was much more important in the early days of audio, when electronic signal paths were significantly different from one another and required a rigorous methodology for meaningful evaluation; today there is a convergence toward a single standard that makes comparative methodology more or less moot. I find myself using the ABX double-blind comparator much less often than I used to, because in most cases I know exactly what the outcome will be; of course, I still have to measure everything to make sure that I am not overlooking significant differences.

Long before you embraced A/B testing, it was clear that you had been seriously thinking about this as a means of comparing gear. Indeed, in the early days of The Audio Critic, you probably devoted more words to discussing this methodological approach than anyone in the audio press—and all this before you were actually conducting level-matched tests. Once you began precise level-matched testing, did you immediately come to a conclusion that all previous thinking had to be revised, or did your conclusions develop in a more gradual manner?

Actually, it was a coup de foudre, or almost. Someone had lent me a simple A/B switching box, without the possibility of level adjustments. I was trying to compare the sound of two completely different preamps which, by a huge coincidence, happened to have exactly the same gain. I couldn’t hear a difference! At first I firmly believed that the A/B box was covering up the difference, but upon further reflection that appeared most unlikely—totally passive, extremely short signal paths, no inductive or capacitive elements to speak of. It dawned on me that the two preamps must actually sound exactly the same. Paul on the road to Damascus... Of course, Mark Davis had told me years before that this is precisely the case, but I made fun of him in print. (Many years later, I met him at an Audio Engineering Society convention and apologized profusely. He didn’t even remember what I was talking about!)

Mark Davis used a pair of AR-11 box speakers and a Shure M-91E cartridge. You were using gear such as the Harold Beveridge electrostatic speaker and more expensive moving-coil cartridges. So at least there was a reasonable presumption that differences in results could have been related to source components. At the same time Davis was matching levels to within 0.3 dB; you indicated that you had level matched to about 1 dB. At the 0.3 threshold he claimed that “differences” were moot. Most audiophiles have absolutely no means to level match components, and hi-fi dealers are not going to do it for obvious reasons. So even though the psychoacoustic literature is clear, the average audiophile is left only with his or her experience. When presented with all the marketing baggage that comes with the territory, it is no wonder that things have not really changed much in the typical audiophile’s thinking. That leaves the burden of getting the message out to the press. You have written about this many times and offered your own reasons for the current state of affairs in audio journalism. Other than the fact that it is often difficult to change one’s way of thinking, is the bottom line simply that it would be bad for business if the truth were known and accepted?

Of course it would be bad for business, at least for the business of Halcro, Mark Levinson, Pass Labs, et al., whose astronomically priced products sound the same as a $200 Pioneer receiver. It wouldn’t be bad for Pioneer, but they don’t absolutely need the publicity of the high-end press. You are mistaken, however, when you say that most audiophiles have no means to level match. A very simple (and superbly ironic) method suggested many years ago by Larry Klein requires no instrumentation and no special expertise. Just play with the level controls of A and B until you can hear absolutely no difference between them. At that point the levels are matched within ±0.15 dB, guaranteed! I still groove on that one.

Your reviews were always different in style than anything else out there. The undergrounds often wrote pages and pages of mind-numbing verbiage. The major publications seemed like they couldn’t wait to finish a review, and they all pretty much read the same. Your style was a mix ranging from humor (the Janis subwoofer) to shock-and-awe total devastation (Infinity QLS). For the subscriber it all made good sense and interesting reading. Do you consciously try and mix your reviewing style for overall effect?

It depends on how I feel. Some audio components elicit from me the utmost seriousness, others contempt or pity, still others laughter. I don’t try to be consistent in my reviewing style. As Bismarck said, konsequent ist ein Ochs—an ox is consistent.

You often had at your disposal gear many audiophiles had heard of but had no reason to own. I’m reminded of your Levinson-modified Studer A-80—a deck one typically finds in a professional recording studio. In a response to a letter from a subscriber you mentioned you once owned Pearl microphones. I take it that over the years you’ve experimented with live recording?

Just a little, on a very few occasions. I don’t consider myself a recordist. That fancy equipment appealed to my gearhead side; the Studer/Levinson was mainly for playing borrowed master tapes. Anyway, nearly all amateur recordists are totally outclassed by the top pros, and I don’t like to be outclassed.